The focus, dedication and teamwork needed to ensure youth sport succeeds

Peter Backeberg

On any given day, all across Bermuda, there are literally thousands of school-aged children running, jumping, kicking, throwing, catching, swimming, sailing or riding with one of the Island’s vast array of youth sport clubs and organisations.

In addition, the Bermuda School Sports Federation (BSSF), as part of Bermuda’s education programme, holds up to 60 tournaments and meets, plus league games, in 10-15 sports each year.

Clearly, time spent on the field of play is an important and influential part of many young people’s lives. Sport keeps them active, teaches important life lessons and can create educational opportunities at overseas high schools and colleges. For those with particular talent and commitment there are also chances to represent Bermuda on the international stage or even enter the professional ranks.

The cultural influence of sport cannot be overstated either, with the community vicariously experiencing the success, or failure, of our athletes, creating a sense of unity, identity and pride. To witness the outpouring of support for Flora Duffy when she romped to victory in the 2018 World Triathlon Series on home turf is to understand the unique power that sport holds in our culture.

But for every Flora Duffy, or Nahki Wells (a professional footballer), there are many, many young people for whom the rewards of sport are defined by simply participating, making friends, experiencing success and failure, staying active, learning teamwork and discipline and developing physically and emotionally as they grow into healthy, productive adults.

It is these young people that Bermuda’s youth sporting organisations are tasked with overseeing and developing in their thousands. This important task can be complicated by another side of youth sport, one where performance is tied to self-esteem and winning seen, and experienced, as a reflection of worth, for the player, their team, their coaches, their family and their community.

Given the shear number of children playing youth sport and the obvious influence of this experience, should there be a national conversation on how to deliver the very best experience for these young people? And what should that conversation be about?

Well, it turns out that conversation is taking place, and while it has been going on in clubhouses and at AGMs for many years, there is now a more formal structure taking shape at the national level, driven by the Department of Youth and Sport in collaboration with the Bermuda Olympic Association (BOA), and others.

The conversation is focused on the idea that the development (physical, social and emotional) of the athlete comes first, and while that may sound obvious, how this is achieved on a consistent basis is less clear.

Despite the best intentions, such altruism faces headwinds from a culture where winning is important, coaching and administration is largely volunteer based and a relatively small pool of athletes is participating in a relatively large selection of sports, all of which are trying to attain success both locally and internationally.

How we measure success might be the most important question facing youth sport today.

In 2019, the Department of Youth, Sport & Recreation released the Sport Recognition Policy which set requirements for Bermuda’s National Sports Governing Bodies (NSGB) and mandated that they all reapply for their designation.

Jekon Edness, the senior sport development officer for Youth and Sport, says that the goal was to create a minimum set of national standards that ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of the NSGBs and to start building a consistent framework across these organisations.

“This is really the first step,” he says. “We knew it would be a shock to some and we didn’t want to be too onerous or overwhelm what are essentially volunteer run organisations, but we do want to set standards to ensure that those bodies that are recognized as NSGBs have implemented reasonable levels of organizational and governance structures that will be checked annually.”

While the new requirements are largely focused on administrative efficiency through governance structure and financial reporting, each organisation must also demonstrate it has “a clearly defined strategy for the development of its organisation and has structures in place to maintain its effectiveness as a NSGB for their respectve sporting activity.”

In addition, Mr Edness says the Department, in partnership with the Bermuda Olympic Association, have begun the process of educating all NSGB’s about the nuances of Long-Term Athlete Development Plans (LTAD), which will be a future requirement for all NSGB’s seeking funding from the BOA and recognition from Government.

“We would like to see NSGBs looking at a six-year-old child who enters their grassroots programme and say, OK, how are we going to get this six-year-old into an elite programme and if they don’t become an elite athlete how do we keep them active in our sport? Not everyone is going to compete at an elite level but at the end of the day you want people to stay active, so you need various pathways for elite athletes and recreational athletes as well.”

In September of 2019, Youth and Sport hosted “ReImaging Sports” a conference designed to prompt the type of dialogue and learning NSGBs can use to develop, amongst other things, their LTADs. The BOA followed with a second set of workshops in January of this year and also hosted an Athletes Forum in February.

The topics addressed at these events speak to some the core issues facing youth sports in countries around the world; how to compete in a healthy way, multi-sport versus specialised training (and at what age) and safeguarding athletes on and off the field.

The urge to compete

“Everyone wants to win,” says Manny Faria, who is in a unique position to comment on youth sport as administrator for the BSSF and chair of the Youth Committee for the Bermuda Football Association (BFA). “But when we focus on winning we can forget about the development part.”

With football being by far the most participated in youth sport in Bermuda, the approach the BFA takes to competition can have a big impact.

“For U7 through U11 we have rules in place to ensure that everyone plays in every game and we don’t keep results or publish scores,” he says. “It has been that way for a long time.

“Three years ago there was a focus group with our Player Development Committee, the technical team and coaches from the clubs and it was determined to keep the younger leagues non-competitive.”

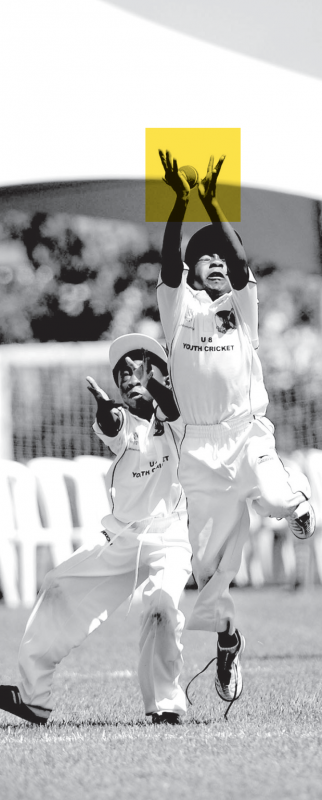

Cricket is another widely participated youth sport and the Bermuda Cricket Board (BCB) takes a similar approach to youth competition.

“We don’t keep results or stats until they start playing with the hard ball at U13,” says Cal Blankendal, executive director for the BCB. “We also play a slightly different format with younger players, a small field, faster play, all designed to get more interaction with the ball.”

Mr Blankendal is also well placed to comment on youth sport having coached youth and senior football since 2002, he holds a UEFA ‘B’ License as a football coach and has run afterschool programmes for middle school boys and girls.

“It’s the parents who make it competitive,” he says. “They might think that what the child does reflects on them. But they don’t always know what instructions the coaches have given the players and are yelling something different to their child. Parents should stop coaching from the sidelines. The kids feel that pressure.”

Mr Faria concurs and says its not just football and cricket.

“I’ve seen it at inter-school sports, parents yelling at their kids, the coaches, the refs. I’ve even seen it community events like Dash in the Dark or the Magic Mile, parents putting pressure on their kids. It takes a mental toll on young people.”

But Mr Faria is also quick to point out that most parents are there to support their children. “I don’t want to paint a bleak picture, for every parent who is yelling from the sidelines there are two who are not, but it’s a challenge.”

Of course winning and losing is part of sport and the very NSGBs charged with developing young people are also looking to identify the next generation of elite talent. Similarly the BOA is charged with identifying and supporting athletes at the very highest level, but are now also supporting NSGBs in their planning for long term youth development.

“The main issue for the BOA is that this is something we’ve never had to do before so we are learning right along with our NSGBs,” says Katura Horton-Perinchief, a former Olympic diver and chairperson of the BOA’s Standards Committee. “To be fair, it is the BOA’s mandate to deal with the elite. The Olympic Games is the pinnacle of athletic success. Developing minors, however, is a whole different ballgame. It’s okay for a young athlete to have an Olympic dream but he or she should not feel like a failure if the goal is not met. Youth sport is and should be about having fun, physical literacy, making healthy lifestyle choices and building confidence.”

With these goals in mind, the role of coaches is critically important. Again, the BFA takes a progressive approach that requires an age-appropriate licensed coach for each team. The license includes not only football training but also First Aid/CPR and SCARS training.

“In boys alone there are 98 teams, so you’re talking about 150-plus, coaches,” says Mr Faria. “I fully support that coaches are licensed and the clubs have embraced it. If the mandate is development it wouldn’t make sense if the coaches themselves aren’t trained.”

While this doesn’t automatically rule out some coaches being overly competitive, Mr Faria says the focus has definitely shifted, “most coaches take it to heart, build relationships and are invested in developing young people in the community.”

The role of SCARS, a Bermudian charity that offers training to adults to build awareness about the “the devastation that child sexual abuse can cause in the life of an innocent child”, has grown increasingly important in recent years.

Patrick Singleton, a three-time Bermuda Olympian, is presently the executive officer of the World Olympians Association and is a member of the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) Medical and Scientific Commission and its Athletes Commission. He says safeguarding athletes, both on and off the field, is a subject of great importance in international circles.

“We’ve seen horrific abuse, most prominently in US gymnastics, but in other sports and other jurisdictions as well.

“To Bermuda’s credit, we are actually ahead of most nations, with SCARS leading the way. It’s a fantastic organisation doing important work.”

At present, Mr Edness says the NSGBs are not required to have coaches SCARS trained and each NSGB sets the standards for their coaches. However, one of the organisations working with Youth and Sport, and therefore the NSGBs, is Positive Coaching Alliance (PCA), a US non-profit.

PCA has been delivering workshops for the NSGBs and also offers comprehensive online training that helps coaches, and parents, to support young athletes, both in terms of developing their full potential and also learning the important life lessons that sport can teach so well.

“PCA provides workshops on the mental aspect of coaching, so it is not sport specific, but more aligned with motivating athletes and getting the best out of them,” says Mr Edness. “Its all about athlete development and retention, making sure we can reach our potential, stay active as a community and improve over time.”

Many sports or just one?

Being a relatively small community that still aspires to achieve at the international level, there can be, understandably, competing interests between the various clubs and NSGBs. They also find themselves bidding for funding from the same pool of resources, whether that’s through the private sector or government.

The quest to develop high quality athletes and demonstrate their success highlights one of the important questions being asked both locally and overseas: Should children be training in multiple sports and at what point is it beneficial to focus on a single sport?

Mr Singleton says this question is not unique to Bermuda, noting that the IOC runs an advanced team physicians course every year, which is attended by chief medical officers from International Sports Federations and National Olympic Committees and big sporting clubs like Liverpool and Bayern Munich, who send their top doctors.

“One of the things they look at is injuries and overtraining. An overarching theme is over specialization at a young age, which can be highly detrimental to the development of young athletes,” he says. “In fact, some top doctors are saying footballs’ many academies are so specialised that a lower than average percentage of players make it from the academies to the pros. Statistically you’ve a better chance coming in off the street.

“When popular sports ‘vacuum’ up a lot of youngsters at a young age it can put a heavy burden on them in terms of training, this can lead to injuries, fatigue and burnout – often many young athletes don’t fully develop and never achieve their full potential as a direct result of over training.”

Sport for Life in Canada is another organisation working with Youth and Sport to help build an athlete development model for Bermuda. Their literature on the subjects clearly recommends a variety of activities that are inclusive and not overtly competitive prior to adolescence. The early and mid-teens are recognized as the critical time for ensuring long-term participation and also identifying and supporting top athletes.

However, even for young people who choose to specialize, Sport for Life still highlights the importance of athletes continuing with “complementary” sports that develop other skills beneficial to their particular sport and physical development in general.

And, on a topic of particular relevance because of Bermuda’s small population, they suggest that sporting organisations work together to ensure success, writing: “A collaborative, coherent approach among coaches, organizations and system stakeholders is needed to support the athlete’s continued development toward excellence, or transfer into ongoing activity for life. When these stakeholders understand the issues and show patience in development, more youth will be retained in sport and physical activity.”

While recognizing the challenges of a small population and that the development curve in each sport can vary, Ms Horton-Perinchief says the best path forward is for the NSGBs to find ways to work together.

“I think the sports can work together if they regard our athletes as our athletes and not their athletes,” she says. “In the off-season for track, kids can swim. In the-off season for gymnastics, kids can dive. The track coach, swim coach and cycling coach can all weigh in on best practice in each discipline for a triathlete. Every little footballer should be doing ballet. The list goes on. It’s a shift in mindset and it’s a change in practice for us. But it can be done.”

Given that the focus of the LTAD is to create pathways for elite athletes and recreational ones too, the benefits of multi-sport training become even more clear and, according to Andrea Cann, a Pediatric Physiotherapist and former chair of Bermuda Physiotherapy Association, can provide a deeper service to the community.

“Multi-sport training is better for younger children, they can find out what they are good at, plus the benefits of sport are well known and young people need them today,” she says. “With the advent of technology kids are less active. We don’t play outside like we used to – climbing trees, riding bikes, taking risks – what I would call ‘outdoor learning’, sports can help re-create that too.”