by Liana Hall

“I was brought up with a sense that if I was going to have a destiny, it might as well be a destiny to lead. Anything short of that is no destiny at all.”– Julian Hall, Bermuda Business, 1991

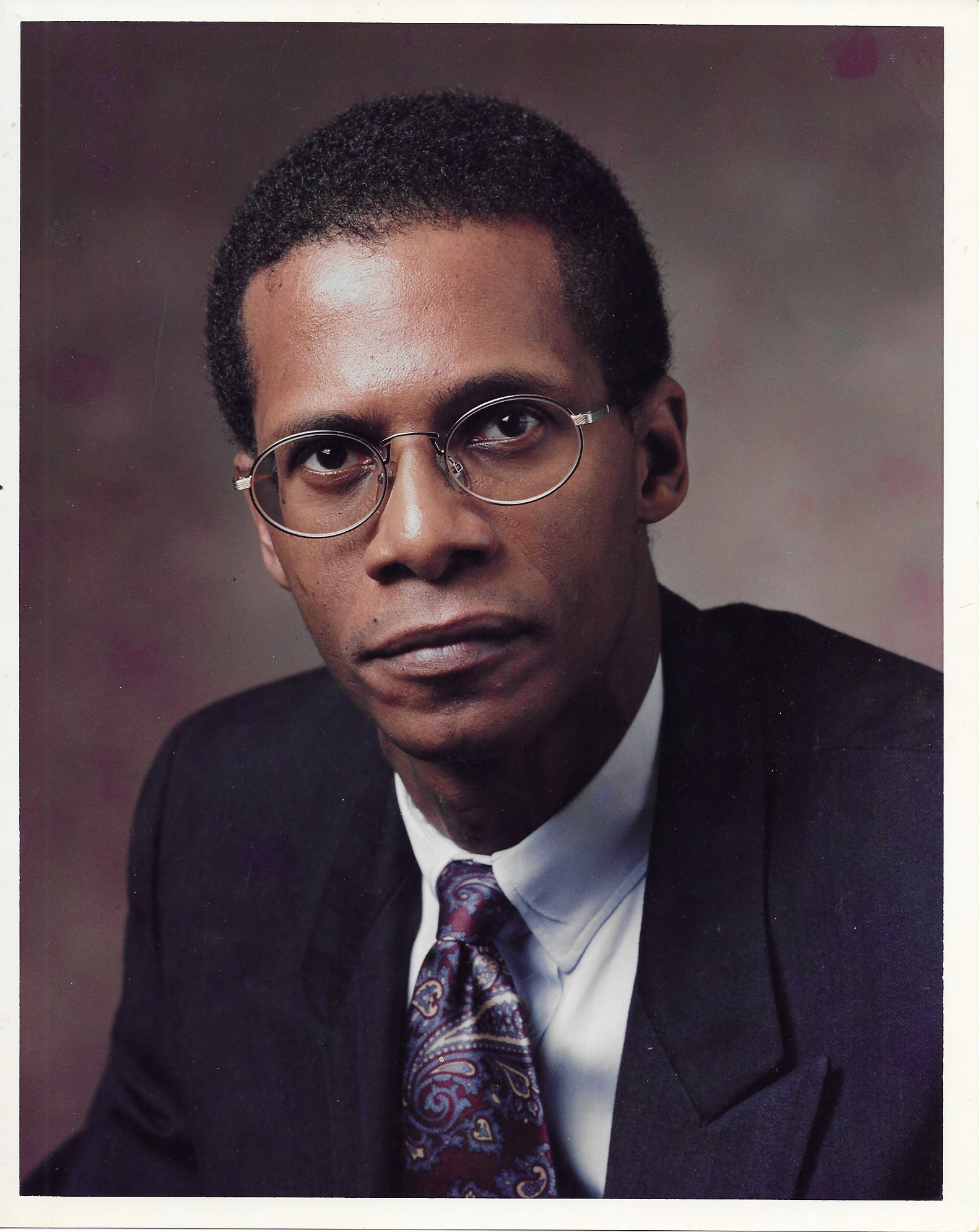

In delivering the news of Julian Hall’s death in July 2009, The Royal Gazette declared my father a “Colossus of Parliament and Courts”. Thousands of words were printed about him, which I consumed in the rawness of grief. They provided solace as I navigated the tremendous loss of a man who was not only my personal hero, but a hero to so many.

This week, I revisited the many words written about and by him during his life. I laughed at his sharp wit, I smiled at his utter brilliance, and I wept as I remembered that heroism is not achieved without sacrifice. His life story rivalled a Shakespearean tragedy – a fitting comparison given his flair for the dramatic. It was present whether he was donning his wig and gown, acting on stage, delivering a parliamentary address, or hosting friends in our home.

The tributes share a similar theme: that he was Bermuda’s great hope, destined to be Premier, but like Icarus he flew too close to the sun, burnt his wings, and crashed into the Sargasso Sea. In The Mid-Ocean News editorial ‘A Bermudian tragedy’ Tim Hodgson wrote that “Julian became the nail that stood too high – the nail that was invariably hammered down.” Having lived through these relentless blows, I understand these sentiments. However, as I reflect on his legacy, my father’s life seems to be a story less of tragedy, and more of triumph.

They came for him. But when the dust finally settled, my father stood bloodied but unbowed.

It is the story of how a poor, bookish, Black boy became a formidable presence whose legal victories set precedent and who in personality, as The Royal Gazette asserted, “was Bermuda’s rock star.” It is the story of a man with such stubborn indomitability of spirit that he was not an Icarus, but a phoenix who perpetually rose from the ashes of the fires set upon him. It is the story of a man who not only knew how to live, but, more importantly, knew how to love. My father’s life was vast. Epic. One cannot encapsulate an ocean in a thimble, so I can share only a few drops.

Dad’s story starts at the poor end of Reid Street where he was raised in a small apartment with his sisters. It was here that his grandmother taught him to treat others with generosity and grace no matter their station or situation. She would add water to the soup to stretch their meal and feed anyone in need: friends or family, prostitutes or drug addicts, strangers, or neighbours. She set his template for life.

The year I turned five, my father was elected as a PLP MP and many of the challenges and victories that had made him an icon were already behind him. Even then, I was conscious of the profound effect he had on people. He threw his considerable intellectual abilities behind the causes that truly mattered, taking positions that were honourable. For this, he was admired and respected, but also feared and despised, reflecting the wildly diverging perspectives of a Bermuda divided along race and class lines.

I had not yet been born when he joined the UBP in 1977 “believing that it was possible to change the system from within” as he told Bermuda Business. I was not yet a thought when he broke party ranks over the executions of Tacklyn and Burrows and assisted Opposition PLP Leader, Lois Browne-Evans in her legal fight to save the two men. There was no twinkle in his eye for me when he battled the Government in the Privy Council and won rights for illegitimate children, setting a precedent still used across the Commonwealth. And yet within my own life, what looms large are the principles that my father and his grandmother held aloft.

Space doesn’t permit me to delve into the full con- sequences of Dad’s decision to “tilt against the UBP windmill” as he put it. Rehman Rashid in Bermuda Business wrote, “More than a few Bermudians saw signs of an establishment hand in the concatena- tion of calamities that had befallen Julian. He had turned his back on those who had groomed him to professional and political prominence, and now he was paying their price.” Or as Dame Lois recalled, “He was their darling and then he ceased to be their darling.”

They came for him. But when the dust finally set- tled, my father stood bloodied but unbowed. After effective banishment from Bermuda, he returned and staged what Rashid termed “an extraordinary comeback”. He galvanised the rank and file through his masterful articulation of their grievances in the House of Assembly and formed a legal team with Delroy Duncan The Royal Gazette deemed “literally unbeatable”. But the machinery of institutionalised racism continued to aim its slings and arrows.

The attacks left him bankrupt. He was denied the right to practice law or stand for election to political office due to legislation designed to persecute him specifically. In derogation of his fundamental right to a fair trial, he was menaced by criminal charges without a hearing for nearly a decade. In 2005, after stunningly representing himself with the able assistance of Charles Richardson, he was unanimously acquitted of theft. The verdict was met with rapturous applause from the gallery and jubilation in the streets.

My father was a staunch trade unionist and never abdicated his responsibility for advancing workers’ rights, representing the BUT and BIU several times. In 2005, I watched him deliver the BIU Banquet speech. He proclaimed, “I don’t want to be part of a movement based on race. I want to be part of a political machine that has belief, principles, that believes in what it’s doing and never forgets its core support, the working people of Bermuda.”

Despite the blows, my father never lost his passion for life, sense of humour, and unbreakable commitment to dismantling our system of oppression. This is how tragedy and victory share the same space at the same time. His life will only become a tragedy if we stop fighting for what he fought for, if we stop championing the cause of the underprivileged, and if we stop telling the stories that matter.