THE HAVANA-BERMUDA HURRICANE KILLED 88 SEAMEN OFF BERMUDA’S SHORE

By TIM SMITH

Claiming the lives of 88 people aboard a British warship, the Havana-Bermuda Hurricane of October 1926 is the deadliest storm ever recorded on the island.

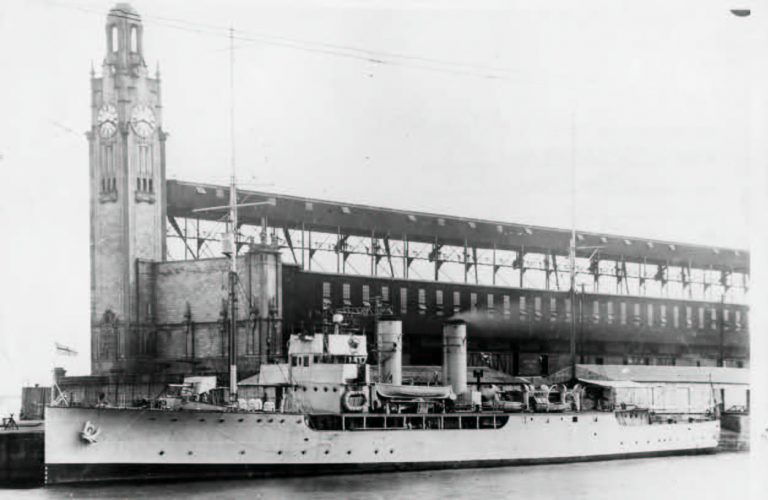

HMS Valerian, returning from a hurricane mission to the Bahamas, was just a few miles away from the safety of port when it was ravaged by devastating winds that caught it by surprise.

Sailors and officers clung to its wreckage for several hours, but by the time rescue ship HMS Capetown arrived the next day, most had been swept to their death.

Many of the victims were known in Bermuda, and the huge amounts of damage the Category 4 storm caused to the island’s infrastructure seemed relatively trivial by comparison.

Commander William Usher, one of just 19 survivors, later told the Court of Inquiry and court martial: “Although wind was blowing with a force of six to seven knots, there was comparatively little sea and I anticipated no difficulty in entering the Narrows, having done so before under similar conditions.

“Indeed, by that time, I felt assured of reaching harbour in safety, as there was no immediate indication of a violent storm, also there was a complete absence of swell that sometimes denotes the approach of a storm.”

Commander Usher could not have been more wrong.

“Here was evidently no ordinary storm. The seas were mountainous and seemed to approach the ship from all sides,” he said.

“At first in fitful gusts and then with a fury that was indescribable.”

He added: “A series of squalls struck the ship on the port side with a fury that beggars all description.

“The helm was hard aport to keep her head to sea, but this was evidently holding her over and on letting go the helm and putting it hard astarboard the ship righted and came slowly up to the wind, wallowing heavily in the trough of the sea as she came round.”

The mainmast and wireless were carried away, the engine stopped and the ship slowly tipped over.

Commander Usher said: “The funnels went under and when the boilers burst a black wave came and

swept me away from the bridge to which I was hanging and carried me under.

“I came up part of the way and bumped my head and after going down again a little, finally came alongside a raft to which I clung.”

Commander Usher, who was left clinging to the repeatedly capsizing raft with fellow survivors for 21 hours, described the situation as “trying enough for the hardest”.

He said: “The 12 hours of night, with waves breaking over us, was an experience never to be forgotten and many gave up during that time. They got slowly exhausted and filled with water and then slipped away.”

The next day, sailors on the Capetown spotted the stricken boat about 18 miles from Gibbs Hill Lighthouse and went to help but, as fierce winds continued to blow, many had died by the time it arrived.

Commander Usher and his men were later cleared of blame at the court martial hearing.

Sub-Lieutenant Ronald Summerfield, the executive officer, was hailed as the outstanding hero of the tragedy, after he went below to rally the troops and order all hands on deck.

He was trapped below deck and went down with the ship.

Another victim, known as gunnery officer Asquith, was described as a popular figure in Hamilton who clung to the raft until he “finally let go too exhausted to maintain his grip within a few hours of the arrival of the rescue party”.

The Royal Gazette reported: “There can be few homes in Bermuda that will not experience the loss of personal friends and many sporting and social clubs will sorely miss the officers and men of the foundered ship.”

The Havana-Bermuda Hurricane, which had already killed at least 30 people and rendered thousands homeless in Cuba before it reached Bermuda, damaged an estimated 40 per cent of structures on the island.

With gusts of more than 160mph, it sank another British ship the Eastway as well as the Valerian, wrecked landmarks such as the Colonial Opera House and Oddfellows Hall in Hamilton and the ancient cedar Old Devonshire Church, and destroyed whole plantations of bananas and lily fields.

There were reports of two men being hurled through plate glass windows, but Terry Tucker wrote in her 1995 book Beware the Hurricane!: “Severe as the damage was to property, compared with the loss of life surrounding such storms in other countries, Bermuda felt herself, as usual, most fortunate.”

A bronze plaque commemorating the 88 people who died on the Valerian was later installed in Ireland Island chapel and is now kept at Commissioner’s House in Dockyard.

Many years later, the storm was remembered as the worst of the 20th century.

Thomas Aitchinson, who was 11 at the time, recalled in 2000: “I could see trees in the distance start to sway and then bend under a terrific wind.

“You could see the storm moving closer by the line of trees bending as the storm hit them. I’ll never forget those trees swaying in the wind like blades of grass.

“You never forget that feeling of the wind going from nothing to being in a great grip of ferocious wind. I remember the rain was torrential.

“The thing I remember most was the cedars. I was amazed to see some big cedars, with trunks two to three feet thick, lying flat on the ground with their roots sticking up in the air.

“They must have been several hundred years old and survived quite a few hurricanes before.”

Roderick Ferguson Sr, another Bermudian, said in 1997: “I was looking out toward White’s Island when I saw three wooden houses uprooted and thrown over the cedar trees.”

One 89-year-old woman recalled venturing outside thinking the storm had finished.

“I didn’t know it was the eye of the hurricane,” she said. “The wind changed and pinned me against a wall. I heard a man was picked up and slammed against the Trading Company window.”