by Tim Smith

As the Atlantic was bombarded by a record 30 named storms last year, at times it felt like they were appearing out of nowhere.

In fact, it takes just a few simple ingredients to form a major storm – warm water, thunderstorm activity, low wind shear and a pre-existing weather disturbance – all of which can be found in the ocean surrounding Bermuda from June to November.

The National Ocean Service in the United States explains that hurricanes often start their life as a tropical wave: a low pressure area that moves through the tropics and causes shower and thunderstorm activity to increase.

Warm air from the ocean rises into this storm, creating another area of low pressure underneath, which in turn causes more air to rush in.

The air rises and then gets cooler so that it condenses back into water droplets which form large clouds.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, those clouds then progress into hurricanes in the following way:

y The water vapour releases heat into the air as it condenses. Warm air rises into the clouds, creating a pattern of evaporation and condensation which causes cloud columns to grow and rise. This pattern causes winds to circulate around a centre, in the manner of water going down a drain. As the system meets more clouds, it becomes a cluster of thunderstorm clouds, or a tropical disturbance.

y The thunderstorm grows higher and larger, and the air at the top becomes cooler and more unstable. Heat energy is released, which warms the air at the top of the clouds and heightens the air pressure. Air rises at the surface of the storm, creating more thunderstorms. Winds in the storm cloud spin at an increasing pace. When they reach 25mph it is called a tropical depression.

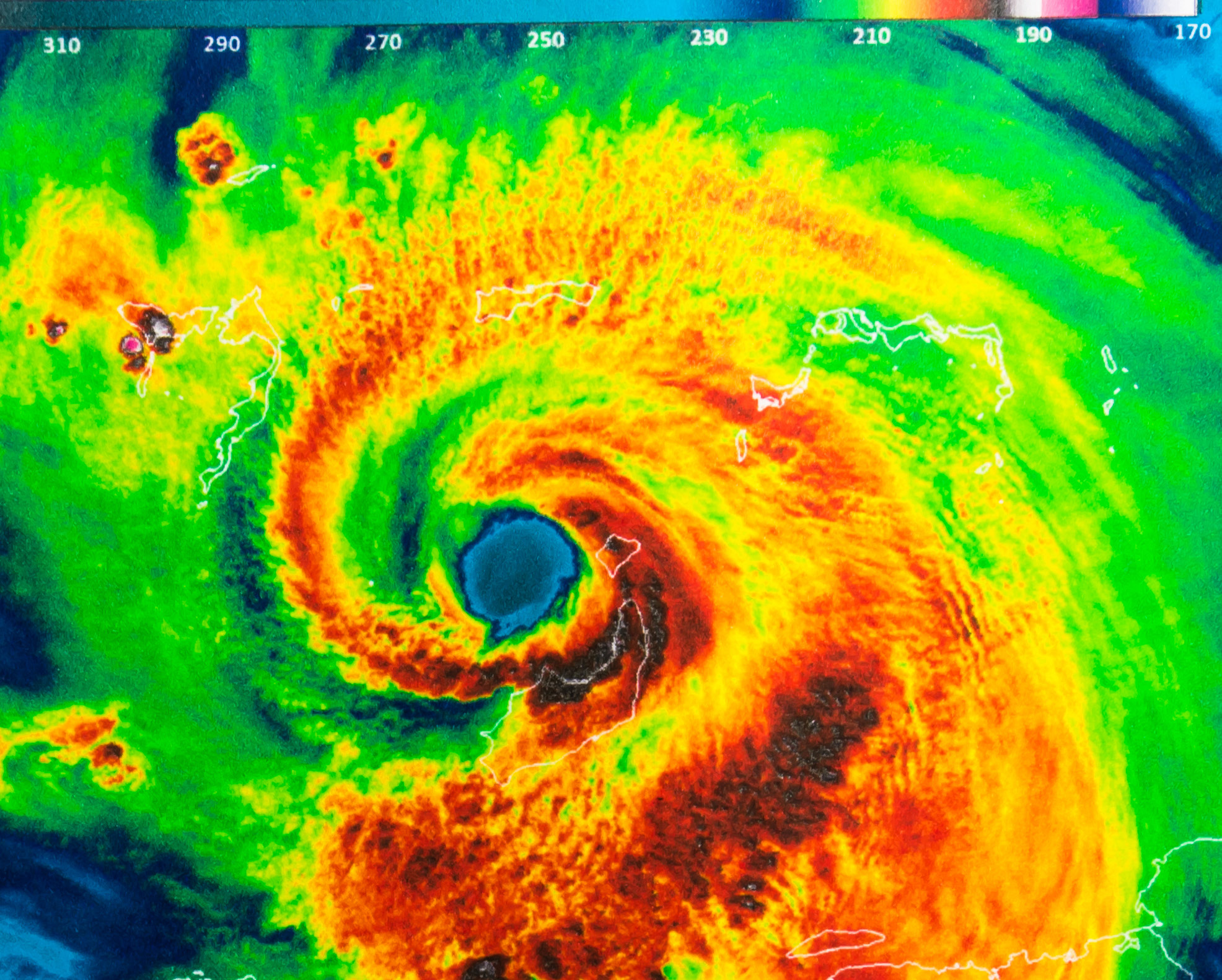

y The process continues as the winds blow faster and twist and turn around a calm centre called an eye. When the speeds reach 39mph, it is called a tropical storm.

y As the speeds reach 74mph, the storm is upgraded to hurricane status. By now it is at least 50,000 feet high and 125 miles wide, with an eye of up to 30 miles wide Bermuda, of course, sits in the firing line of the tracks of Atlantic hurricanes.

Mark Guishard, the director of the Bermuda Weather Service, said: “As hurricanes develop in the deep tropical Atlantic and move from east to west, they can begin to drift northwards slightly.

“If this northward drift is sufficient for them to move out of the steering flow provided by the trade winds, then they are more prone to recurve around the Bermuda-Azores high pressure system into our part of the Atlantic and get picked up by the westerly steering flow.”

Lying in a region that straddles the tropics and the mid-latitudes, Bermuda is susceptible to hurricanes in the summer, and maritime conditions such as cold fronts, winter gales and extratropical storms in the winter.

Dr Guishard said: “Bermuda’s position in the subtropical western Atlantic makes it fascinating for meteorologists like myself.

“Its geology, size and isolation from any major land masses makes it somewhat resilient to these phenomena – there’s no long continental shelf to amplify storm surge, and the fringing coral reef serves to break up the worst wave action.

“The frequency of larger scale events such as hurricanes and winter storms perhaps makes for a resilient mindset, based simply on practice. That being said, Bermuda does sit in the firing line of the tracks of Atlantic hurricanes, and we must not allow our historical relatively good fortune to enable complacency.”

While not as unpredictable or intense as a hurricane, winter storms remain an annual source of concern for Bermuda residents.

“A strong winter storm may be as powerful as a weak hurricane,” Dr Guishard said.

“We have seen a number of those systems in the North Atlantic this past winter – some causing hurricane force gusts.

“Often, these extratropical systems also have embedded thunderstorms that can exacerbate the wind speeds and gusts as they move through the area.”

Dr Guishard said that Bermuda experienced a particularly stormy winter in 2020-21 because the polar vortex has been weak, which allowed cold Arctic air to spill further south than normal.

“In our part of the world, this in turn causes a cold North America and a windy North Atlantic,” he said.