HURRICANE OF 1839 LEFT FAMILIES HOMELESS

by Tim Smith

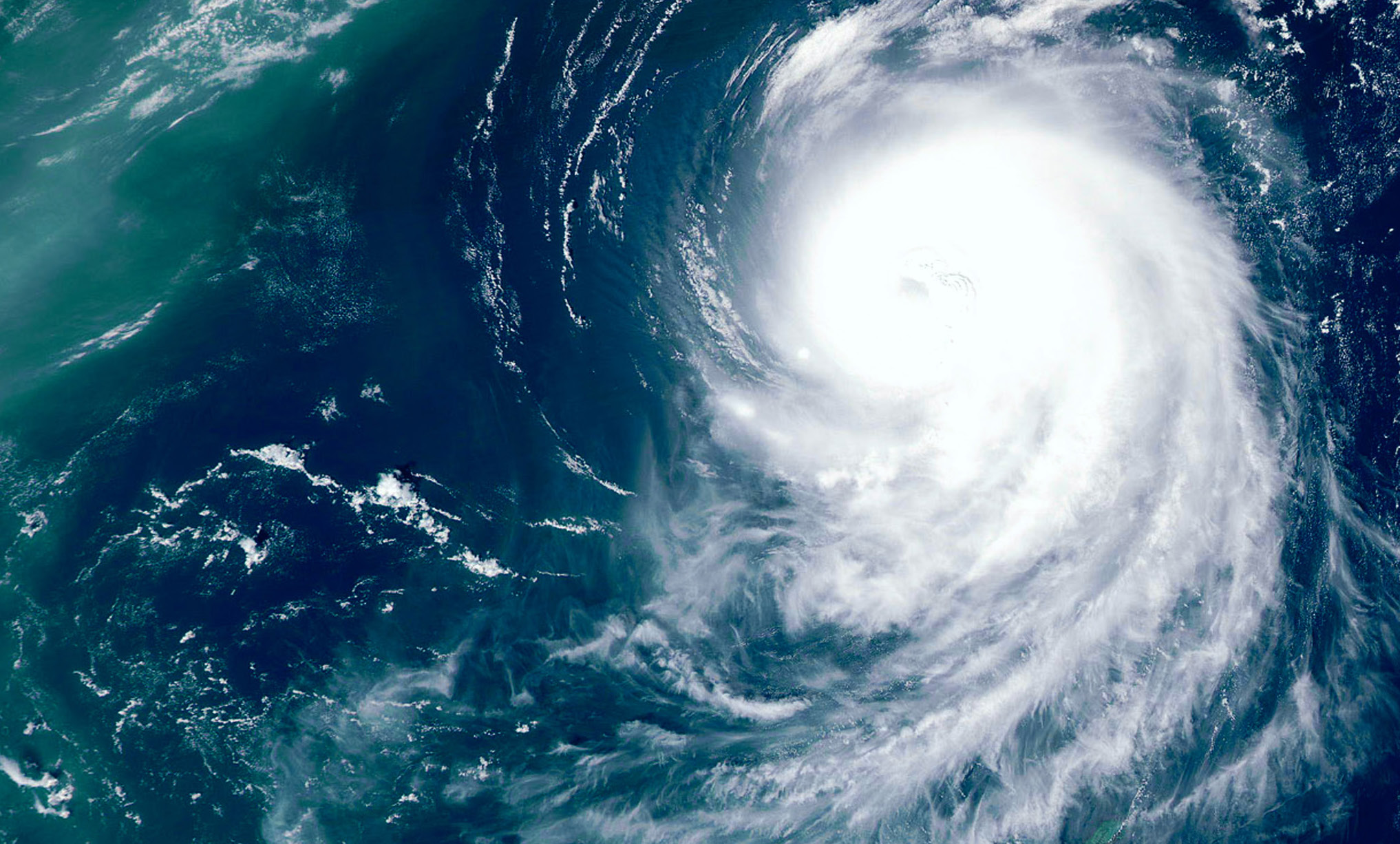

For centuries, the hurricanes that wreaked devastation on communities in the Caribbean and East Coast were largely blamed on storm gods.

All that changed, slowly but surely, with the emergence of meteorology in the 18th and 19th centuries – and Bermuda was at the heart of the scientific revolution.

The great storm of 1839, which left many families homeless as it ravaged properties across the island, played a key role in breaking down the mystery of hurricanes thanks to the scientific governor of the time, Sir William Reid.

Some even credit Sir William with helping limit the impact of that storm: while it destroyed huge numbers of homes, miraculously nobody was killed.

Certainly, his detailed analysis of weather conditions before and during the storm, which he shared with fellow scientists across the world, led to it being dubbed “Reid’s Hurricane”.

The storm, on the night of September 11, was one of the worst to hit Bermuda in the past 200 years.

Many families were forced to ride it out in the open air because their houses were so badly wrecked by atrocious winds, and an estimated £8,000 of damage was caused to private homes alone – the equivalent of more than $1 million today.

One cottage was even picked up, blown across the road and dumped in a field.

“It has never fallen to our lot to record so violent and seriously calamitous a hurricane,” The Royal Gazette reported in its first edition after the hurricane.

“We have heard of several instances where whole families were driven from their dwellings to pass the night in the open air, exposed to the pitiless pelting of the storm, in such shelter only as the rocks afforded – in the cellars beneath their tottering and falling houses, or to seek refuge in the shattered residence of a more fortunate neighbour.”

The newspaper continued: “Sad indeed was the appearance of our parish on the noon of Thursday. Scarcely a house escaped injury, some were levelled and others unroofed and the sides walls rent to the foundation – walls and fences in every direction prostrate.”

The Gazette told of one “extraordinary event” in which a cottage near Town Cut in St George’s “was taken by the wind bodily across the road and lodged in a field some distance on the other side, breaking down several cedar trees in its progress”.

Commissioner’s House and the naval hospital were among the buildings severely damaged in the West End, while island-wide properties to suffer included Hamilton Bakery and the tower at Tower Hill.

Thousands of stately cedar trees were torn up, along with orange, lemon, lime, peach and banana trees.

Salt spray from the South Shore was carried more than a mile inland and the water in all tanks across the island was contaminated with salt water. Species of fish were found hundreds of yards from the shore.

The Gazette conceded its report was merely “an outline of this direful visitation” and added: “To particularise would be a preposterous attempt when almost every house in the Bermudas has in some way or other shared in the general destruction.”

Describing the terrible impact on families, the Gazette reported: “We are assured by persons who have been among some of the poorest of the sufferers that what these have endured and are still enduring is beyond description. Harrowing to the feelings are the tales of misery which are told.”

Sir William had only arrived in Bermuda a few months previously.

A former lieutenant in the British Army, his interest in hurricanes was piqued when he was sent to Barbados to lead reconstruction efforts after the great storm of 1831, which killed more than 1,400 people.

He gathered data from that disastrous event and combined it with information from logbooks of British ships before publishing his book, An Attempt to Develop the Law of Storms by Means of Facts, in 1838.

The book, which demonstrated how hurricanes moved in circular paths, was so well received that Sir William was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge.

Terry Tucker’s 1995 book, Beware The Hurricane!, reports that within weeks of Sir William becoming governor of Bermuda, the Gazette had introduced a meteorological register to record weather data.

Tucker also notes the newspaper’s report of the storm “shows more scientific knowledge than previous storm records” because of Sir William’s influence.

She reports how residents had known the hurricane was coming for two days, because of a swell rolling to the south, and the muddy colour of the sea.

Some have also speculated that Sir William’s theories had enabled people to predict the direction of the wind and find appropriate shelter.

Sir William documented the great hurricane of 1839 and shared details with his international colleagues. He also used his experience of the storm to write his second book, Progress of the Development of the Law of Storms, in 1849.

His contribution to Bermuda went much further during his tenure from 1839 to 1846, and earned him the label “The Good Governor”.

A biography, reported in The Bermudian in 2018, notes that Sir William, whose term began five years after Emancipation, “did not believe in a racially divisive society and had no patience with the whites, especially the poor whites, who would not adjust their attitudes and lifestyles to the new situation created by the abolition of slavery”.

He heralded education as the solution to social problems, founded Bermuda’s first library and urged the Legislature to spend as much money as it could afford on educational facilities.

Sir William was also a strong believer in agriculture, founding the Ag Show in 1841 and helping to transform Bermuda’s fruit and vegetable export business.