by Vejay Steede

On September 5, 2003, Bermuda experienced the most devastating hurricane to hit these shores in many decades. Hurricane Fabian was the big one; a tempest that relentlessly hurled wave after wave of anger and carnage at our small island home, and put us on our knees for the better part of a month.

Not only was Fabian one of the most destructive hurricanes Bermuda has ever endured–causing some $300 million in damage to our infrastructure–but he was also the deadliest storm to hit Bermuda since 1926. We’ve seen nothing like Fabian since; and we don’t want to see anything like him again!

The most tragic part of Hurricane Fabian was the heartbreaking loss of three members of the Bermuda Police Service and one civilian when all four lives were swept away from the Causeway in St. George’s by carnivorous seas and ravenous winds.

We still remember and honour the memory of Constable Stephen Symons, Constable Nicole O’Connor, Station Duty Officer Gladys Saunders and Mr. Manuel Pacheco, who was an employee of the Corporation of Hamilton.

These four courageous souls were not the only ones on the Causeway on that fateful afternoon though, and this is the very first time a voice who was there has spoken about the experience. This is, of course, a very traumatic and sensitive episode in our collective history, which makes this testimony so very important.

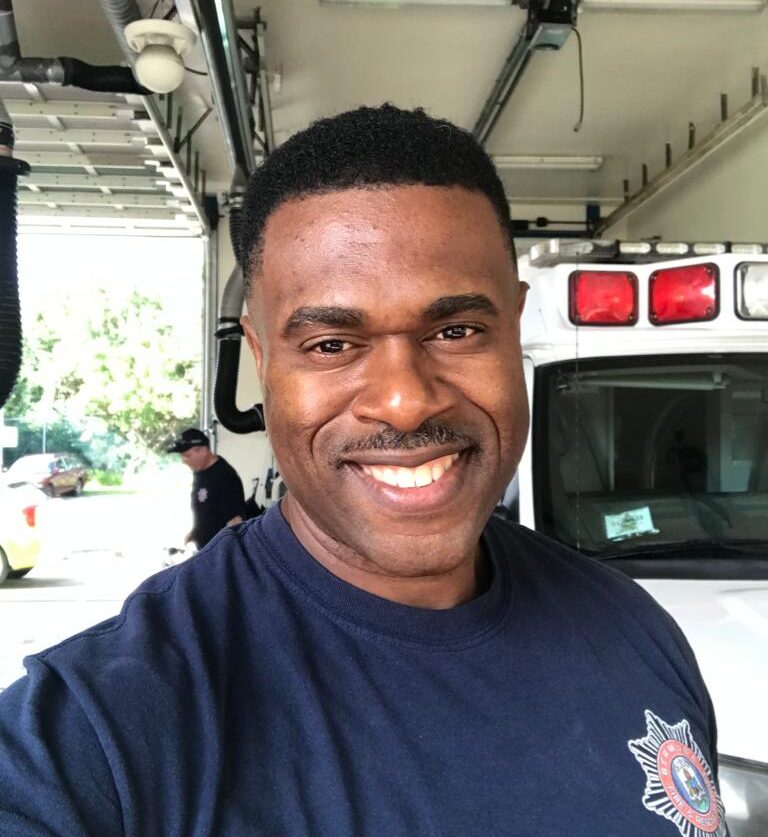

Bermuda Fire and Rescue Service Engines were dispatched from both the Clearwater Station and Hamilton Station in an emergency attempt to save the lives trapped on the Causeway that day. Leroy Maxwell was a member of the Hurricane Rescue Crew, Clearwater Division, and rode to the scene on Clearwater 1.

“The mission was to rescue four persons trapped in two vehicles rendered immobile on the Causeway. Each vehicle had two persons trapped and unable to exit their vehicles due to high waters and engine stall. There was no additional information available because the connection was lost during the 911 call from the casualties, and there was poor visibility and heavy debris blowing overhead,” Maxwell remembers.

“The waves were at least 10 to 15 feet high and crashing over the bridge, which presented a challenge for rescue vehicles to pass onto the bridge and continue on towards the stranded parties.”

The six-member crew, led by Sergeant Wendell Simmons, and comprised of firefighters Carl Govia, Lionel Furbert, Maxwell Burgess, Michael Medeiros and Maxwell himself, proceeded to make a brave effort to reach the trapped individuals.

“Due to high winds and waves, we were unable to know how far away the casualties were located. Moreover, no distances, times or measurements were made available due to the abrupt loss of connection from downed lines,” Maxwell says.

“After assessing the last transmission from the 911 dispatchers, it was assumed that the victims were located just beyond the [Longbird] bridge on the western side, leading towards the Causeway. Right there and then, it was decided that rescue was needed, and we made a plan to use a lead rope–tied from our Clearwater fire truck–as an anchor, attaching each firefighter to that rope. The plan was simple, make our way towards the casualties until we were able to make visual, retrieve them, and then make our way back.”

This amazing crew of front-line rescue workers, with zero visibility, made the on-the-spot decision to trek down a narrow strip of man-made land with violent seas and swirling winds threatening their very existence. It takes your breath away just thinking about it.

The plan was a solid, if simple one, but the odds were not in the crew’s favour, and Fabian was not prepared to cooperate with their mission objective that day. Maxwell continues: “Unfortunately, it did not happen. The first wave came over the bridge and swept us right towards the open ocean. I witnessed Sergeant Simmons get swept away first, then a huge wave knocked me right off my feet and wedged me up against a rock. A second and a third wave pinned me down, and I was unable to move until a break in the surf created a window of opportunity for me to make a run for it,” says Maxwell.

“We were all saved by the hand of the sea Gods, and took refuge in a small, abandoned pump room conveniently located on the bridge. A second window of opportunity gave us a chance to double back to our rescue vehicle, and there we stayed until the call was made to head back to the station and regroup. Unfortunately, our plan was foiled, and we were not able to rescue the stranded victims.”

The rest of the story has become an indelible part of Bermudian hurricane folklore, but Maxwell’s account and recollection of events during Hurricane Fabian raises many points of interest. This was clearly a futile effort at an impossible rescue, and we have since solved the problem of hurricane rescues on the Causeway by closing the dangerously prone piece of thoroughfare whenever Bermuda is threatened by a serious storm, but knowing that our rescue workers made this attempt is somehow quite comforting.

The fact that they were able to retreat and survive the deadly event is very auspicious indeed, and the unfortunate reality that casualties were sustained does not diminish the heroic attempts made by these officers.

This was not as much a “failed rescue” as it was a sobering reminder that hurricanes are not to be played with. Our rescue workers are highly skilled and very capable of keeping us safe. To know that they are willing to blindly venture into a whistling corridor of death to attempt an emergency rescue should provide considerable peace of mind.

This story of survival is a blessing, a testament of hope and a powerful justification for the trust we put in our front-line rescue workers. We have, rightfully, eulogized and celebrated the casualties of Hurricane Fabian; we must also honour the survivors.