Bermuda is known the world over for its vernacular architecture and the diverse range of bright colours that adorn its buildings and houses, so it might be surprising to learn that many of our house colours are a relatively new adaptation.

In fact, the rough-hewn “Cabbens” that many of our ancestors inhabited in the early 1600s were not painted at all, as they were most likely constructed of simple cedar frames covered with a stucco composed of whatever raw materials were available (such as lime, clay, sticks, sand, and turtle or shark oil) – and a roof thatched with Palmetto leaves.

According to The Traditional Home Building Guide published by The Department of Planning and The Bermuda National Trust however, by the I8th century “roofs, walls and even woodwork were regularly coated with limewash, which looks white or dull grey, as protection against the weather” and it is thought that even the palmetto roofs may have been painted on a regular basis.

LIMEWASH: THE FOUNDATION OF PROTECTION

Limewash is created by burning crushed limestone in a kiln and subsequently “slaking” or soaking it in water. The resulting slaked lime is meticulously sieved to eliminate lumps, and additional water is added to achieve a fluid and manageable paint consistency. The limewash is traditionally applied using a course straw brush and must be constantly stirred to prevent solid particles from settling at the bottom.

Even though limewash gave buildings an irregular and slightly shabby appearance unless it had been newly applied, it was a crucial element for preserving the early stone buildings that define Bermuda’s architectural landscape.

LEAD WHITE: A HAZARDOUS YET DURABLE PIGMENT

One of the earliest pigments to be introduced in Bermuda was lead white. Despite its toxicity, it was mixed with linseed oil to create a robust paint for both interior and exterior woodwork. Lasting four to five years, lead white paint disintegrates into dust over time, thus simplifying the preparation for a fresh coat as there is little need for scraping. Due to its toxicity however, its use was discontinued in the 1970’s.

INTRODUCTION OF COLOUR: 18TH CENTURY

Although it is unclear when Bermudians first began to apply coloured pigment to their houses, it is clear that the trend had taken hold by the last third of the 18th century as prints and watercolours from the early 19th century depict a spectrum of colours, including: yellows, browns, reds, and washed-out blues.

Imported pigments, such as ochres, burnt sienna, burnt umber, and Venetian red, were blended to produce a range of earth tones, providing a vivid contrast to the island’s blue skies and turquoise waters. One theory even suggests that in the Victorian Era British soldiers stationed on the island at the time, used random paint colours from their supply ships to fix up their cottages, thus encouraging the practice to catch on.

IMPORTED PIGMENTS AND LOCAL INNOVATIONS

It is worth noting that these early pigments were often imported in their crude form (rocks, earth, bone, and minerals), and were then ground into powders, before being blended with appropriate mediums.

In Bermuda’s isolated setting, it is likely that enterprising locals also concocted their own recipes using locally sourced pigments and there is evidence to suggest that burnt Bermuda clay was mixed with limewash to create yellow-brown or light brick hues – while indigo (which was grown in Bermuda), may have been mixed with white to produce a bluish-grey tint in the 18th century.

TRADITIONAL BERMUDA COLOURS – A DISTINCTIVE PALETTE

The traditional colours for external woodwork in Bermuda were distinctive and practical. Dark green, believed to be a mixture of two parts “Verdigris” (copper salts) to one part lampblack in oil, was used on blinds, doors, and window frames. Flat white was reserved for the windows themselves, providing a crisp contrast against the lush greenery of the island. Occasionally, a medium blue was introduced to woodwork in the 19th century, showcasing the evolution of Bermuda’s architectural aesthetics.

GIVING THE EXTERIOR OF YOUR HOME AN AUTHENTIC MAKEOVER:

Bermuda’s house paint colours tell a tale of adaptation, creativity, and resilience. From the simplicity of limewash to the introduction of imported pigments and local innovations, the island’s architecture has evolved in harmony with its natural surroundings.

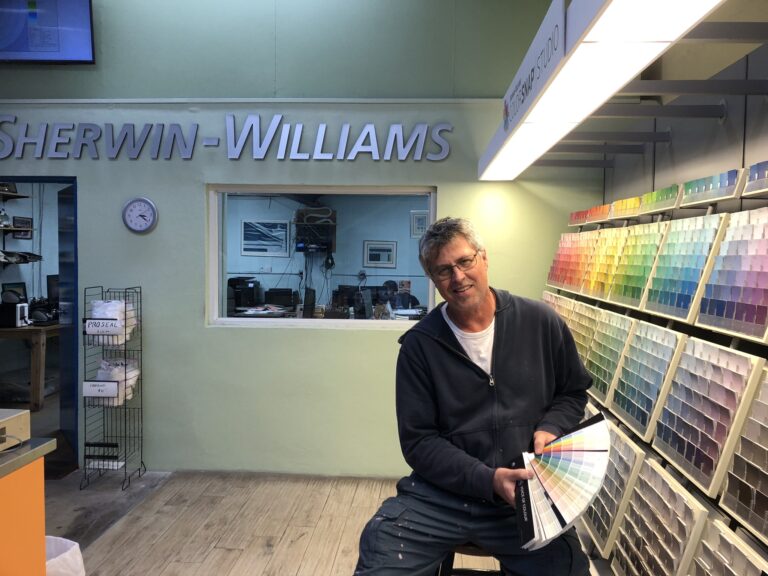

Thanks to a project sponsored by Pembroke Paint Company Ltd., researchers from Texas AM were able to analyse the composition of the layers of paint on several of the Bermuda National Trust houses including Verdmont, Tankfield, and Tucker House and then matched the data collected to colours currently available in the Sherwin Williams colour collection.

“Interestingly, the research revealed that most of the early paint colours were quite muted in comparison to the colours that are popular today,” says David Swift of Pembroke Paint.

“Modern paint is water based so there is very little risk of encountering lead paint,” says Mr. Swift. “But proper prep work is essential because each layer of paint that is added to a house increases the overall weight of the paint on the building which in turn increases the likelihood that it will crack and pull away from the building allowing water to seep in.”

Mr. Swift offers the following advice for anyone planning to repaint an old Bermuda house:

• Always start by inspecting the exterior of your dwelling to look for mildew and cracks.

• Water is the enemy of old Bermuda stone and plaster, so it is essential to gently scrape, bleach and fill all cracks before repainting.

• Really old Bermuda homes sometimes have a foundation layer that is chalky or even resembles “cottage cheese” – these need to be treated with special primers and sealers – so ask for advice before proceeding if you come across this.

• Houses built near the water typically accumulate a salt coating on their exterior, while houses located near a main road tend to accumulate soot. This needs to be cleaned off before any priming or painting can take place.

• If you are uncertain exactly what colour your house has been painted, you can scrape a paint chip off the building and bring it in for a free spectrographic analysis to enable it to be colour-matched with a currently available paint colour.

For Further Information Contact: David Swift – Pembroke Paint 292-8368