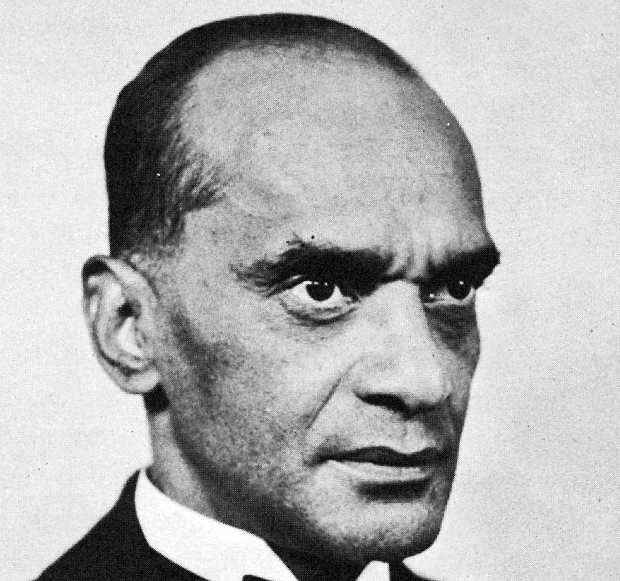

After he was elected president of the Bermuda Workers Association in July 1944, Dr EF Gordon wasted no time putting his stamp on the fledging union.

He was a physician, not a tradesman, and a foreigner to boot, having arrived in Bermuda 20 years earlier from the Caribbean. But the BWA founders had recruited him to be their president because of his oratory, outspokenness and take-no-prisoners approach in dealing with the 40 Thieves, the powerful white men who controlled every aspect of Bermuda.

When he controversially won a seat to Parliament in a St George’s by-election two years later, he had two platforms on which to fight for “the voiceless, voteless and underprivileged masses of Bermuda”.

Dr Gordon had promised that, if elected, he intended to take a petition to the UK Government on behalf of the BWA, calling for the establishment of a Royal Commission to investigate social and political conditions in Bermuda.

He did just that. In Freedom Fighters—From Monk to Mazumbo veteran journalist Ira Philip wrote: “He was bypassing the Governor and his Council, as to petition them about existing conditions was tantamount to appealing to Caesar’s wife concerning Caesar.”

FIGHT FOR RIGHTS

The petition was not the first from Bermuda. In 1931, suffragette leader Gladys Misick Morrell had presented the UK Government with a petition calling for a Commission of Inquiry to investigate the lack of voting rights for women. Nothing came of that, although female property owners would eventually win the right to vote in May 1944.

Dr Gordon, who was from Trinidad, had taken his cue from the Caribbean, which had held Royal Commissions since the 1930s. The wide-ranging BWA petition tackled systemic issues, such as segregation and the feudal voting system, which dated back to the 1600s. It had the backing of the BWA membership, which had grown to 5,000 in two years.

The BWA executive drew up plans for the petition during the summer parliamentary recess, Dale Butler wrote in Dr EF Gordon—Hero of Bermuda’s Working Class. In September, the BWA launched a series of 12 public meetings to win the support of its members.

Mr Philip wrote that, at the meetings, BWA members were not required to provide signatures in order to protect them from economic intimidation from “employers, landlords and creditors”. They demonstrated their support with a show of hands.

The meetings received extensive press coverage. Mr Philip said The Royal Gazette “was fairer” than the Mid-Ocean News. He added that Letters to the Editor were anti-Gordon in the main and editorials were “sparse”.

BATTLE FOR REFORM

BATTLE FOR REFORM

The petition had 18 signatories, including well-known activists and tradesmen such as WER Joell, Robert A Wilson, Allan Russell and Dudley Seaton; Doris Cholmondeley and Althea DePina were the sole female signatories.

The petition presented a compelling case for reform: only seven percent of the population had the right to vote; the civil service was closed to Blacks; education was compulsory from ages 7 to 13 but not free; Black nurses could not work at King Edward VII Memorial Hospital; there was no worker’s compensation, unemployment insurance or health insurance; voting was restricted to property owners who had the right to vote in every parish where they owned land.

In November, Dr Gordon travelled to London to deliver the petition to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, rejecting an offer from the Governor to send it to the UK on his behalf. In London, he received assistance in his mission from two law students who would go on to make their mark in Bermuda: Earle Seaton, the future judge and son of signatory Dudley Seaton, and future premier ET Richards.

Dr Gordon was in London for five months. On his return, he waited for a response from the UK. It came on March 30, 1947. Command Paper 7093 contained the full text of the BWA petition and a decidedly unsupportive memorandum from Bermuda’s Governor. But the UK Secretary of State stated in his response that he “could not escape the conclusion that the petition called for serious and early attention”.

RALLY FOR CHANGE

Days after the Command Paper was made public, Dr Gordon held a rally at Bernard Park. He was highly critical of the Governor, who had referred to him in his memorandum as an “immigrant from Trinidad”. “We must not forget,” Dr Gordon told the rally, “that His Excellency is an admiral and that is why he was so much at sea about local conditions.”

Parliament debated the Command Paper and agreed to establish a Joint Select Committee. But with only two Blacks on the 12-man Committee, the outcome was predictable.

When the Committee released its report in March 1948, Dr Gordon described it as “trash” and an “insult to the majority of this country”. The report was debated in Parliament over several sittings in April 1948.

On the first day of the debate, placard-bearing BWA supporters, in an unprecedented display of solidarity, demonstrated on the grounds of the House of Assembly. According to The Royal Gazette, about 300 people “mostly coloured”, packed the public gallery and entrances. One MP described the debate as the most notable since 1834 when slavery was abolished.

In the end, Dr Gordon’s reaction would prove to be correct. The only tangible result was free primary school education, which became a reality in 1949.

Despite that setback, Dr Gordon would continue fighting for change until his death in 1955, 70 years ago this year. In 1959, the successful Theatre Boycott would deliver a fatal blow to segregation, achieving in two weeks what parliamentary committees had failed to achieve.

The first election held without a requirement to own property took place in 1963, although property owners had an extra “plus” vote until the 1968 election, the first under full universal suffrage.

The BWA petition, which is housed in the Bermuda Archives, is a remarkable document that gave an unsparing depiction of an inequitable economic and political system that disadvantaged Blacks and working-class Bermudians of both races.

It is reprinted in its entirety in Mr Butler’s book which, along with Mr Philip’s book and The History of the Bermuda Industrial Union, were key sources for this article.